After roughly 1,650 miles in the back of a climate-controlled shipping truck, the Lucy Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (L’LORRI) for NASA’s Lucy mission arrived on Monday, Oct. 26, at Lockheed Martin’s doorstep in Denver.

It’s the first of the Lucy spacecraft’s three instruments to arrive — and it showed up in the middle of a snowstorm.

“Sometimes it seems like the gods are against us,” joked Dewey Adams, the APL program manager for L’LORRI. “Nothing on this program happens easily.”

For the past year and a half, the team has wrestled through managerial issues, technical problems, and the challenges and restrictions of COVID-19. When APL first received the instrument from a collaborating company in April, nearer to the pandemic’s start, L’LORRI was already 11 weeks behind schedule.

Despite quarantines and schedule challenges — and by working every weekend and holiday for the last six months — the APL L’LORRI team pulled that 11-week delay down to three.

“Normally, once you get to the integration and test phase of a project, you start slipping schedule, not getting it back,” said John Wilson, the lead engineer for the L’LORRI program. “It took a huge effort from everyone on the team to get that delivery date back down.”

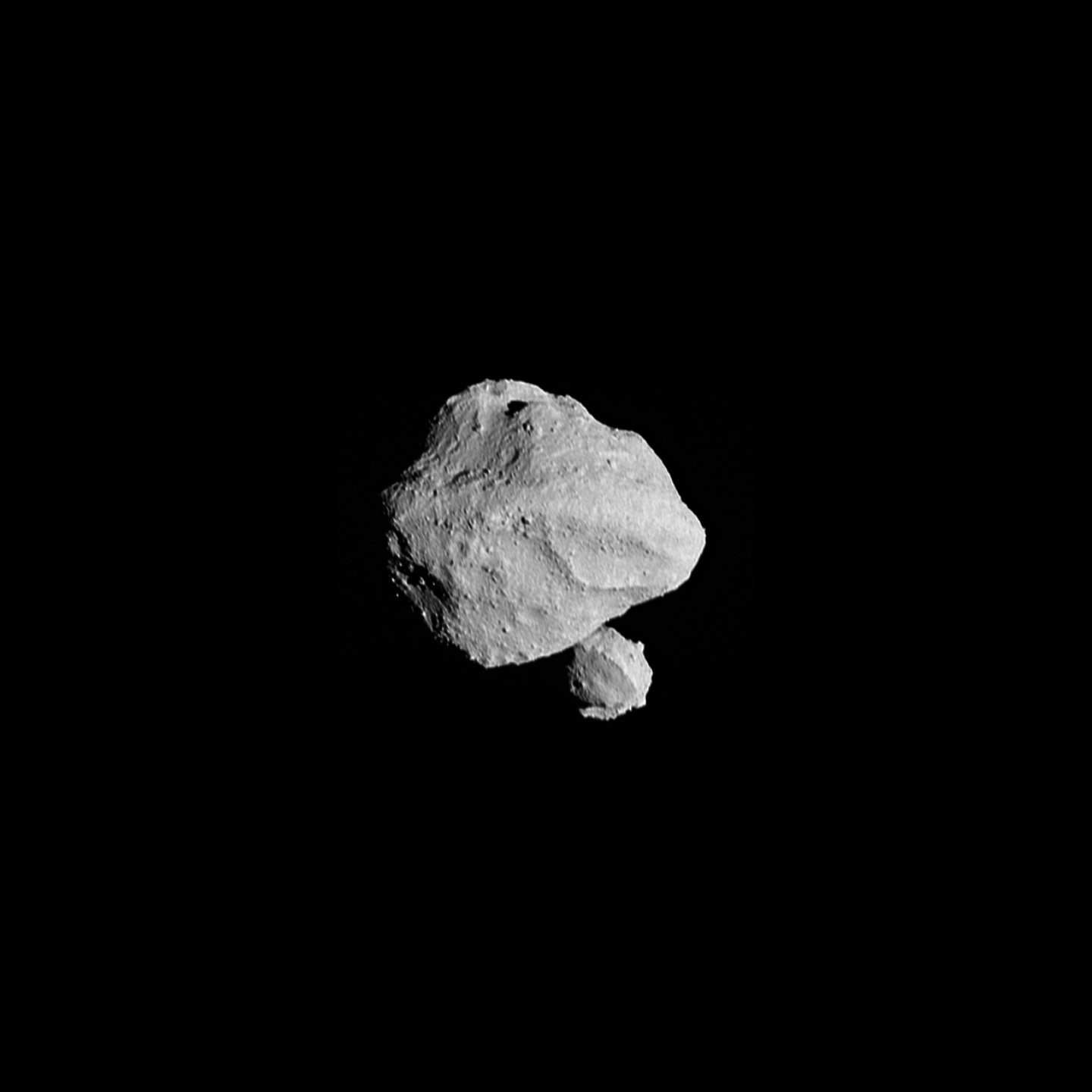

L’LORRI has a critical role in the Lucy mission, a mission led by the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas, that will explore at least seven never-before-seen asteroids called Trojans. These small bodies orbit the Sun at the same distance as Jupiter, forming two clumps: one ahead of the planet and the other behind. They are relics from the solar system’s beginning, 4.6 billion years ago, when they were likely scattered throughout the outer solar system. And they’re expected to provide information about the processes that shaped the early solar system, including the period when the giant outer planets were migrating within the solar system and caused the Trojans to clump into their current positions.

Nearly identical to its predecessor LORRI that provided the first images of Pluto from NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, L’LORRI is a high-resolution imager that serves both as a long-range navigational system for the spacecraft and as a scientific camera that will provide detailed pictures of the Trojan surfaces. L’LORRI has the ability to clearly capture an elephant-sized object from more than 600 miles away.

L’LORRI does this using two mirrors to direct incoming light toward its detector. Unfortunately, the larger mirror was inadvertently distorted while being polished, causing the telescope to produce images with significant astigmatism. This optical flaw wasn’t caught until November 2019, but rather than wait 10 months for a new mirror, the L’LORRI team replaced the bad mirror with a spare one from New Horizons LORRI.

“We didn’t think we’d actually have to use that mirror from New Horizons,” said APL planetary scientist Hal Weaver, who is the principal investigator of the L’LORRI instrument and the project scientist for the New Horizons mission.

Retrieved from its box, which has been collecting dust at APL since 2004, the New Horizons backup mirror was cleaned, polished, tested and approved — and now is riding on the new LORRI instrument.

“It’s a bit of the old and a bit of the new,” Weaver said.

But then came the pandemic.

As the program manager, Adams said most of his time was spent trying to coordinate, communicate and ensure people punctually got the materials they needed, all through the buzz and dings of emails and video calls.

“You don’t realize the value of a five-minute conversation in the hallway until you can’t do it anymore,” Adams said. He also had to navigate the unpredictable schedules of the team members, many of whom have children to pick up or care for, spouses or partners who also work, or health conditions that made catching COVID-19 particularly unnerving.

The team worked parts in parallel, temporarily expanded the work schedule from two shifts to three shifts, and shifted priorities if they couldn’t finish their primary objective for the day, always trying to get something done until the instrument was complete.

“It just seemed so surreal seeing the actual instrument ready to go when I still remembered it as a CAD drawing in a proposal so long ago,” Wilson said. “I just really didn’t believe it.”

Wilson took a flight out to Colorado, where he has been working on getting the instrument integrated with the spacecraft for the past week. “After we get this installed and tested on the spacecraft, I’m taking the rest of the year off,” he said.

All eyes are then on its launch date in fall 2021.

To Weaver, that’s really the most important part of all this. “Delivering the L’LORRI instrument — that was our job. But what we’re going to learn about the formation of the solar system by observing these Trojans, that’s what we’re really looking forward to participating in.”

Harold Weaver

Related Topics

For Media Inquiries

For all media inquiries, including permission to use images or video in our gallery, please contact:

Michael Buckley

All Media Resources