As it orbits the Sun, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe encounters some of the most challenging conditions ever faced by a spacecraft: temperatures up to nearly 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit (800 degrees Celsius), space dust that could easily degrade materials and instruments, and intense light and high-speed particles escaping from our closest star.

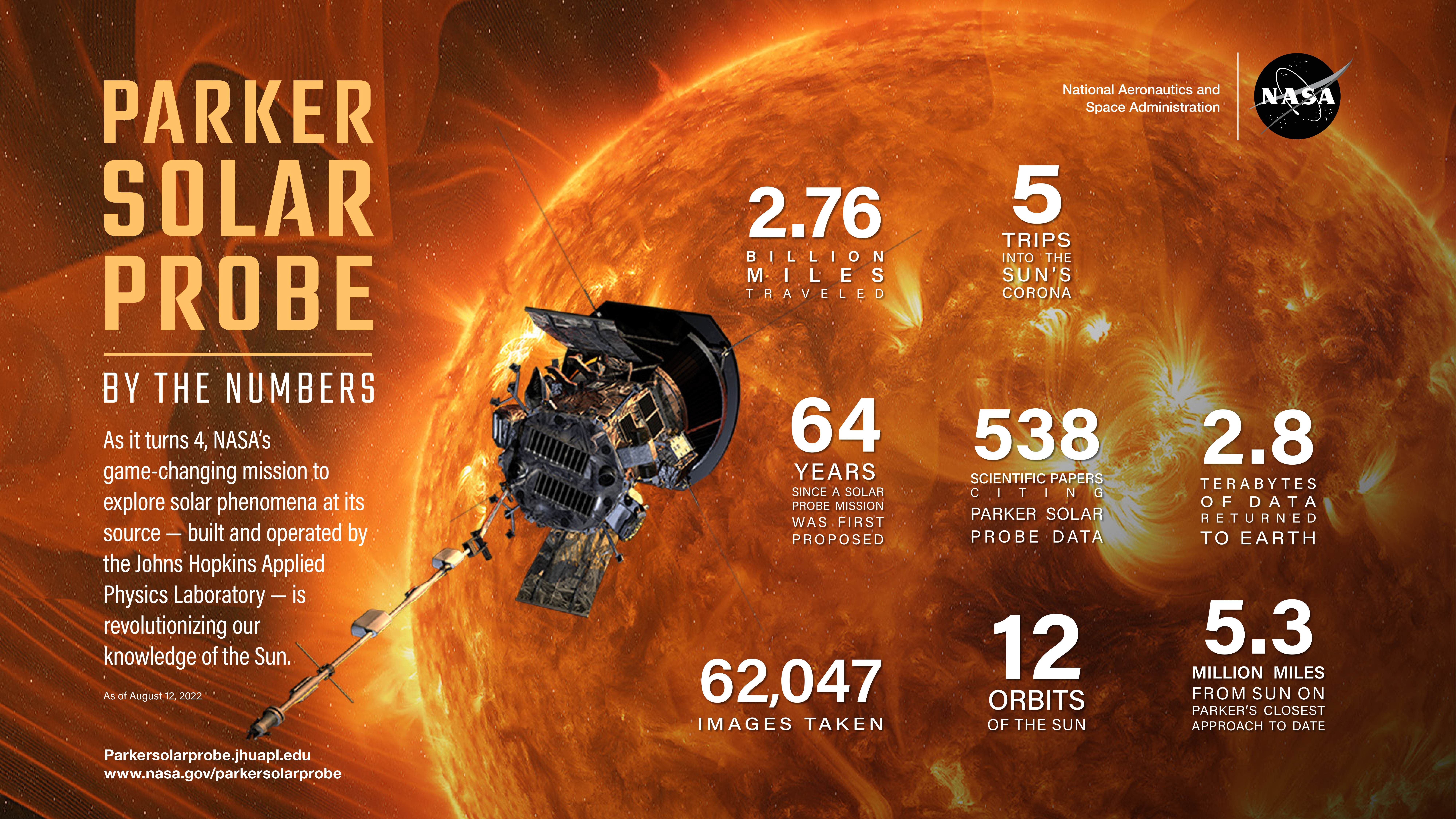

But four years after launch, the spacecraft is operating exceptionally well and sending back more than twice the planned amount of scientific data.

“Despite operating in such an extreme environment, Parker is performing well beyond our expectations,” said Helene Winters, Parker Solar Probe project manager at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. “The spacecraft and its payload are making spectacular observations that will revolutionize our understanding of the Sun and the heliosphere, and that is a testament to the innovation and tireless dedication of the team.”

Building a spacecraft to withstand these conditions for years was a monumental challenge. The mission team at APL had to prepare the spacecraft to operate in an environment that had never been explored before. Parker has weathered it all while flying approximately 2.7 billion miles (4.4 billion kilometers) — roughly the distance from the Sun to Neptune — and doing it faster than any mission before. By comparison, NASA’s New Horizons — the APL-led mission that captured the first images of Pluto — took 8.5 years to fly the same distance.

“We designed to worst-case assumptions for things like the thermal environment and the effects of solar radiation on the spacecraft,” said Jim Kinnison, the Parker Solar Probe mission systems engineer at APL. “We’re pleased that all the hard work during the design phase to define those worst-case assumptions has paid off.”

The spacecraft’s stellar performance has opened the door for the team to optimize the amount of science returned from the mission.

“Our telecommunications links are more robust than our worst-case predictions, allowing us to downlink at higher bit rates,” said Kinnison. “As a result, the scientists have been able to collect and downlink about three times more data than planned before launch. This means we’re able to study the Sun in more detail during each encounter but also greatly increase science return when we’re farther away. It also means we can collect data in special circumstances like Venus flybys, well beyond our basic science objectives.”

Over the course of the mission, Parker has sent back roughly 2.8 terabytes of scientific data, approximately equivalent to the amount of data in 200 hours of 4K video. Scientists worldwide will use this data for years to come to develop a better understanding of the Sun’s effects on Earth and our solar system.

“Mission operations have gone exceedingly well over the course of the mission,” said Nick Pinkine, the mission operations manager at APL for Parker. “The spacecraft and instruments are very healthy, and the teams involved continue to support the operations of this very complex mission with superior expertise, maximizing science return.”

Next month, Parker will complete its 13th perihelion, its closest approach to the Sun in this orbit. During that encounter, it will fly through the Sun’s upper atmosphere, the corona, for the sixth time.

That environment, though, is only getting more extreme. Parker makes its 13th approach as the Sun’s activity ramps up prior to solar maximum in 2025 — activity that NASA has reported is already exceeding predictions. This means there are more sunspots, solar flares and solar eruptions than predicted. However, according to John Wirzburger, the Parker spacecraft systems engineer at APL, the team is not concerned about the spacecraft’s continued performance.

“Parker was designed to handle things like radiation and solar flares,” he said. “As some of the bigger solar flares have been released, the spacecraft has weathered the storm each time without issue.”

“Exploration is inherently risky, but the spacecraft has proven to be robust and able to autonomously keep itself safe,” added Kinnison. “We’re looking forward to the rest of the mission, and that closest perihelion at the end of the primary mission.”

Related Topics

For Media Inquiries

For all media inquiries, including permission to use images or video in our gallery, please contact:

Michael Buckley

All Media Resources