An analysis of large salt deposits on Mars indicates that ponds of liquid water existed on the red planet for about a billion years longer than previously believed.

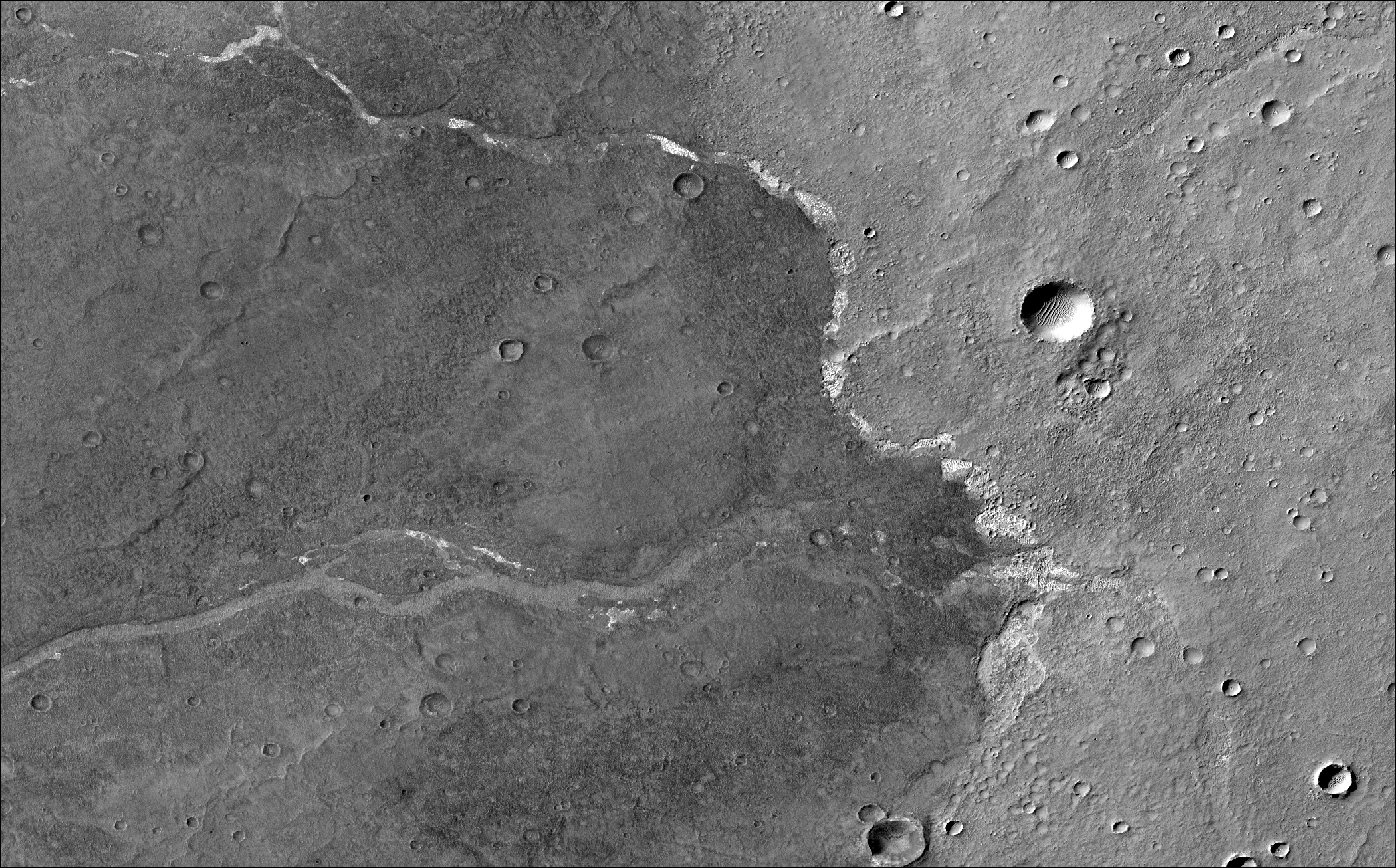

Hundreds of deposits of sodium chloride (table salt) stretching tens to hundreds of square kilometers in area were discovered by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) starting in 2008. Not only did they offer evidence that Mars had been much wetter long ago, but they also offered a way to date the last time that water had existed in liquid form on the planet’s surface.

“Salt is incredibly soluble, so any moisture at all would dissolve it,” said Ellen Leask, lead author of a paper examining the deposits that was published by the journal AGU Advances on Dec. 27. “As such, these deposits must have formed during the evaporation of the last large-scale water on the planet.” This work was part of Leask’s doctorate at Caltech; she is now a postdoctoral researcher at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland.

The discovery of the salt deposits presented two questions to scientists: how did they form, and how old are they? To address those questions, Leask and Bethany Ehlmann, Caltech professor of planetary science, analyzed the salt deposits, looking at what types of landforms they formed on and how they were deposited across the terrain.

Using data from MRO (including imagery from the APL-built Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars instrument, called CRISM), Leask and Ehlmann conducted a broad study of all of the known salt deposits and found that they are surprisingly thin — less than three meters thick — and occur in topographical lows that drape across the landscape.

“They don’t fill basins like salt deposits in Death Valley,” said Ehlmann, co-author of the AGU Advances paper. “The closest analog we can find on Earth are chains of lakes that you get in Antarctica when snow melts seasonally atop permafrost. It cannot penetrate deep into the frozen ground below, so when water evaporates, the salt deposit left behind is thin.”

The Martian salt deposits are often found in shallow depressions, sometimes perched above much larger craters that are devoid of the deposits. This orientation would seem to indicate that the water came from surface runoff during a freeze-thaw cycle of ice, with chloride for the salt leached from the top of clay-rich soils, according to the paper.

Leask and Ehlmann found the chloride deposits atop volcanic terrain that formed as recently as 2.3 billion years ago. Previously, it was believed that large-scale liquid water on Mars ceased to exist around 3 billion years ago.

“This offers us new targets for future missions to Mars,” Leask says. “Some of these deposits are on terrain that’s a billion years younger than the ground the Perseverance Rover is rolling across right now, really extending our idea of when water last flowed across the Martian surface.” Future missions could analyze the textures of the chlorides to confirm that they are indeed the result of evaporation and also learn about what organic compounds might have been associated with the water when it existed.

The paper is titled “Evidence for Deposition of Chloride on Mars From Small-Volume Surface Water Events Into the Late Hesperian-Early Amazonian.” This research was funded by NASA and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Related Topics

Science

For Media Inquiries

For all media inquiries, including permission to use images or video in our gallery, please contact:

Michael Buckley

All Media Resources